As usual, Krugman has a more nuanced and appropriate view on public debt and interest rates. I quote it in full:

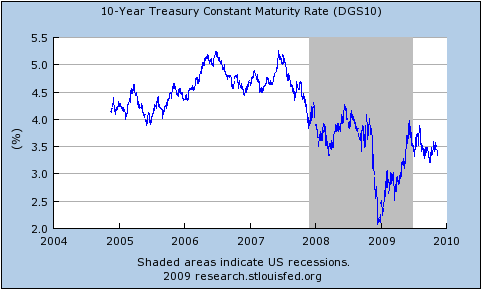

On the face of it, there’s no reason to be worried about interest rates on US debt. Despite large deficits, the Federal government is able to borrow cheaply, at rates that are up from the early post-Lehman period, when market were pricing in a substantial probability of a second Great Depression, but well below the pre-crisis levels:

Underlying these low rates is, in turn, the fact that overall borrowing by the nonfinancial sector hasn’t risen: the surge in government borrowing has in fact, less than offset a plunge in private borrowing.

So what’s the problem?

Well, what I hear is that officials don’t trust the demand for long-term government debt, because they see it as driven by a “carry trade”: financial players borrowing cheap money short-term, and using it to buy long-term bonds. They fear that the whole thing could evaporate if long-term rates start to rise, imposing capital losses on the people doing the carry trade; this could, they believe, drive rates way up, even though this possibility doesn’t seem to be priced in by the market.

What’s wrong with this picture?

First of all, what would things look like if the debt situation were perfectly OK? The answer, it seems to me, is that it would look just like what we’re seeing.

Bear in mind that the whole problem right now is that the private sector is hurting, it’s spooked, and it’s looking for safety. So it’s piling into “cash”, which really means short-term debt. (Treasury bill rates briefly went negative yesterday). Meanwhile, the public sector is sustaining demand with deficit spending, financed by long-term debt. So someone has to be bridging the gap between the short-term assets the public wants to hold and the long-term debt the government wants to issue; call it a carry trade if you like, but it’s a normal and necessary thing.

Now, you could and should be worried if this thing looked like a great bubble — if long-term rates looked unreasonably low given the fundamentals. But do they? Long rates fluctuated between 4.5 and 5 percent in the mid-2000s, when the economy was driven by an unsustainable housing boom. Now we face the prospect of a prolonged period of near-zero short-term rates — I don’t see any reason for the Fed funds rate to rise for at least a year, and probably two — which should mean substantially lower long rates even if you expect yields eventually to rise back to 2005 levels. And if we’re facing a Japanese-type lost decade, which seems all too possible, long rates are in fact still unreasonably high.

Still, what about the possibility of a squeeze, in which rising rates for whatever reason produce a vicious circle of collapsing balance sheets among the carry traders, higher rates, and so on? Well, we’ve seen enough of that sort of thing not to dismiss the possibility. But if it does happen, it’s a financial system problem — not a deficit problem. It would basically be saying not that the government is borrowing too much, but that the people conveying funds from savers, who want short-term assets, to the government, which borrows long, are undercapitalized.

And the remedy should be financial, not fiscal. Have the Fed buy more long-term debt; or let the government issue more short-term debt. Whatever you do, don’t undermine recovery by calling off jobs creation.

The point is that it’s crazy to let the rescue of the economy be held hostage to what is, if it’s an issue at all, a technical matter of maturity mismatch. And again, it’s not clear that it even is an issue. What the worriers seem to regard as a danger sign — that supposedly awful carry trade — is exactly what you would expect to see even if fiscal policy were on a perfectly sustainable trajectory.

And one last point: I just don’t think the inner circle gets how much danger we’re in from another vicious circle, one that’s real, not hypothetical. The longer high unemployment drags on, the greater the odds that crazy people will win big in the midterm elections — dooming us to economic policy failure on a truly grand scale.

No comments:

Post a Comment